The first time that author Sarah Levy tasted a strawberry, she was 3 years old. “The fruit,” she writes, “was so delicious that I snuck handfuls when my parents weren’t looking, devouring the berries until I made myself sick. One of my earliest memories is from that night: lying on the couch, queasy, with berry stains on my fingers. I couldn’t understand how something that tasted so good had wound up making me feel so bad.”

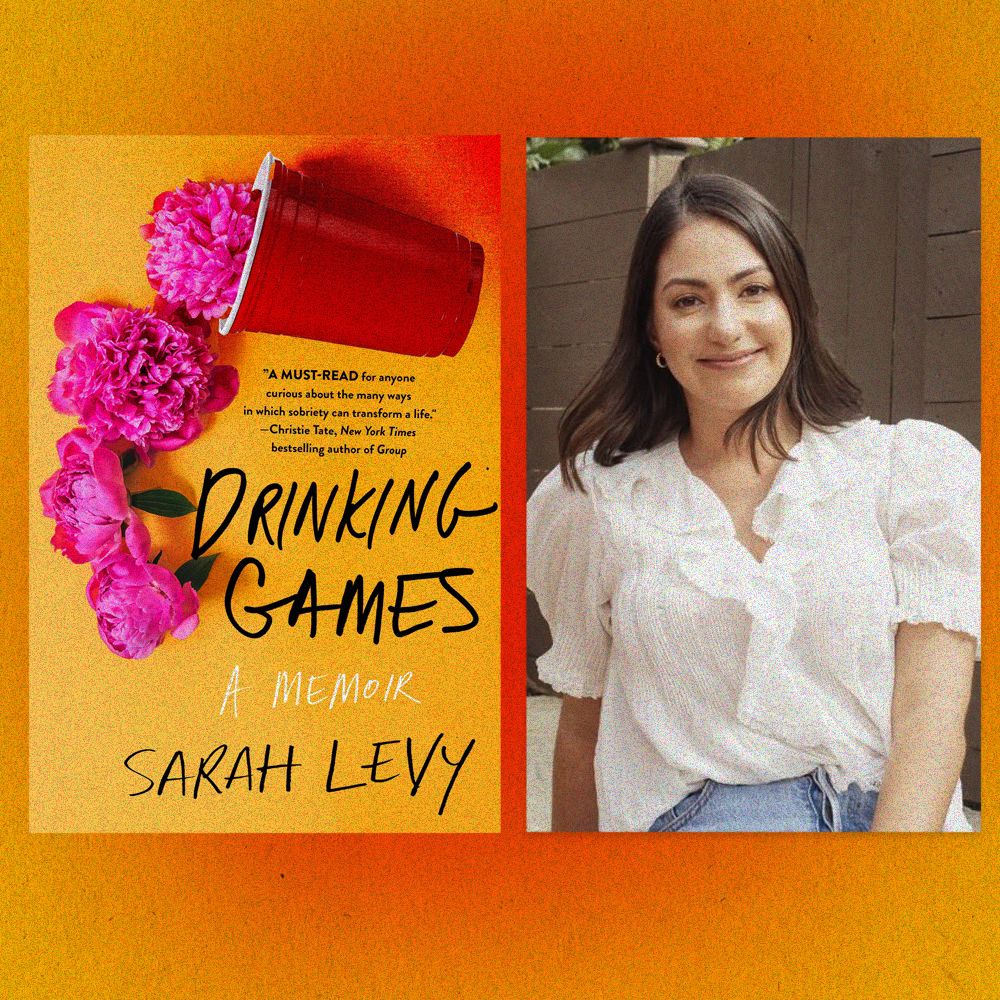

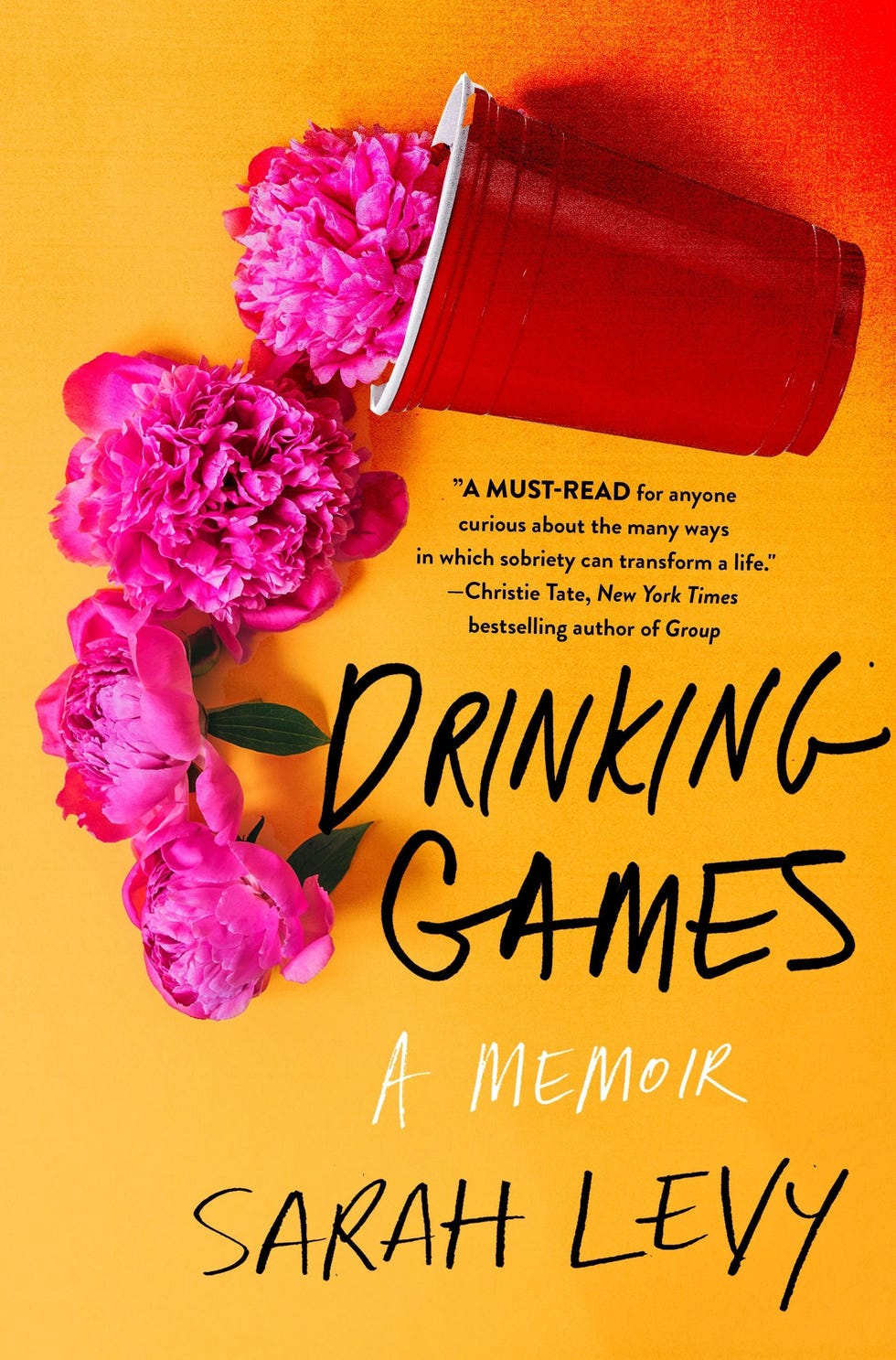

You’d be hard pressed to find a better description of Levy’s alcoholism and subsequent road to sobriety in her deeply moving new memoir in essays, Drinking Games. Recounting her journey from being blackout drunk nearly every night to being sober for more than five years in brutal, unflinching detail is exactly what makes Levy’s debut memoir so effective and important. Not only does Drinking Games work as a well-written, honest look at the dangers of alcoholism (and the joys of sobriety), but it also serves as a beacon of hope for those who may also be struggling with their own addiction.

Shondaland recently caught up with the author to discuss her memoir, being a reliable narrator, vulnerability, living one day at a time, and so much more.

SCOTT NEUMYER: You say in the book, “I have always had the urge to lie,” and you talk quite a bit in the book about lying and secret keeping, which is common for folks dealing with addiction (and even some, like me, dealing with anxiety). With that propensity to lie, how can your readers know that you’re a reliable narrator? How can they know they’re getting the “real Sarah” in this book?

SARAH LEVY: That’s a really good question. You know, I think that my lies were always designed to make everyone think that I was okay, and to make it seem like I had it all figured out, and that everything was perfect. The meat of the book — the story that I really set out to tell — was the truth. It was that I wasn’t okay, I was not perfect, and that I was struggling. I think that my friends and family, even now, if I say, “I’m fine. Everything is good,” that’s usually when I’m not telling the truth, because I’m a human being, and there’s usually something going on. In recovery, I’ve learned how to have perspective and gratitude. Even on days where things might be challenging, I can say, “I have my health, and I have my family, and things are okay.” So, it’s not to say that every day is horrible, but if I’m like, “Everything’s great, and things are perfect,” that’s usually when I’m being dishonest.

The book is raw. There’s a lot that I write about that I don’t know that I would have the guts to say to someone in person face-to-face, but I think the act of writing provides a little bit of a cocoon. It’s like you’re just talking to the page, and then you’re able to have this intimate dialogue with readers without having to be face-to-face, which for someone with anxiety also can be a little bit scary.

So, I think the short answer is that the book sheds light on some really messy and unpleasant and uncomfortable and ugly moments in my life, and I had never shared those with anyone before. The lies I was telling were always the glossy versions. It was denial. And I had to get honest with myself about my drinking and the addiction that I had developed with alcohol. I had to also start getting honest about the way that I was living my life in other areas.

SN: Your being super-open and raw in this book is one of the things that I think makes it work so well. It’s a brutally honest look at your experiences with drinking and recovery. Now that it’s done, and it’s out in the world, do you feel like you ever held anything back? Or do you really feel like you bared your whole soul here?

SL: I was thinking about it this morning, so it’s funny that you ask. I do feel like I bared my whole soul. And yet, there are a couple of things that I feel like I kept to myself that I didn’t dig into. This is my first book, and I hope to write others, and I think there’s other material that I would love to continue to explore and really look at.

I actually wrote an essay recently for Time that talks about the secrets and the lies. Something that I mentioned in that essay is that I was sexually abused when I was 6 and 7, and I actually don’t go into it in detail in the book, for various reasons. I didn’t want that to be the focal point of the story. It’s not a story about childhood sexual assault. It’s about my drinking and what that looked like. So, that is one area I made the decision not to go too heavy or too deep into it in the book. But other than that, I really tried to just leave it all on the page and tried to bare my soul and talk about all the things that I really would have wanted someone to share when I was struggling with my drinking.

SN: A reader can feel there’s a real vulnerability in the book that comes along with opening yourself up so much. One of the first quotes that I wrote down from the book was “I have always cared too much about what other people think.” How has that feeling affected you? Do you think you’ve made strides to overcome this on your path to sobriety? This isn’t the first time you’ve written about these subjects, but a full book probably feels different, yes?

SL: Yeah, absolutely, a full book definitely feels different. When you write an essay here or there and put it out in the world, drip by drip, people are doing things in between reading. They’re not just sitting down and reading your whole story. It’s definitely scary. I would be lying if I said, “Oh, yeah, I don’t care at all what people think.” There’s definitely some nerves. I hope that people like it. I hope that people can relate to it. But most of all, I really do hope that it can help someone. And that is really the mindset that I’m going into the release of the book with. I have no control over the outcome, right? We never have control over what people think of us, what people are gonna say. And I’m sure that there’s going to be some people who will read it and maybe not relate to it. But mostly, in my heart of hearts, I just really hope that it reaches someone who’s struggling the way that I struggled, even if the details are different, or the way that we drink may be different, or maybe it’s drugs someone’s struggling with. I hope someone can identify with the feelings and can see that there’s another way. That they don’t have to drink every day, or they don’t have to use drugs; they don’t have to be a slave to that cycle.

I do feel like I’ve made strides in that area in recovery. The obsession to be liked, and to be accepted, has very much lessened for me. And that’s also probably a function of getting older. But of course, it’s always there, especially with something as vulnerable as writing and putting your work out into the world and wanting people to buy your book. That metric, in and of itself, is like an extension of people validating you, so I think it’s complicated. I don’t think it’s possible to say, “Oh, I don’t care at all,” but I’m trying to toe the line.

SN: The format of the book itself is super-interesting to me as well. It seems to be the way to go these days, the memoir in essays. What is it about that format that you think works so well for this story? And was there ever a time when you thought perhaps you’d write a more traditional memoir instead?

SL: Yeah, absolutely. I originally thought of having it be a traditional memoir, but ultimately, there are a couple of reasons I went in this direction instead. One, the memoirs that I love to read that are more in the traditional format (going from childhood to adulthood) are usually written by celebrities or people who I’m really curious about, and it often shows their ascent to a certain place in their life. I didn’t feel like I was writing a memoir of the story of my life. I really wanted to focus on my drinking and recovery, and it didn’t make total sense to start that story in childhood. I do talk about experiences and memories that I had as a child, but I really wanted to focus on different areas that were impacted by my drinking and sobriety, like my relationship with my body, wellness, my family, my friendships. I felt like doing it in a traditional memoir format would be jumping around a lot.

I also felt like I wanted someone to be able to pick up this book while hungover or on day two of sobriety and feel like there’s hope right away. A lot of the other drinking stories or memoirs — recovery memoirs — that I read, the solution (or the recovery arc) started toward the end. You’ve had to make it through a lot of drinking stories to get there. And I really wanted someone to be able to pick it up and read the introduction and be like, “Okay, there’s another way,” and feel some relief.

I also liked the idea of going back and forth. There is some repetition that’s intentional. There is some going back in time and kind of figuring out where we are in the timeline because that was how I drank for 10 years. It was like, “I don’t know what’s going on. I don’t know if I’m gonna stop for good.” The experiences that I had in the month of not drinking would have a real impact, and then I would start drinking again. It was all the same timeline for me, so I felt like essays would just allow me to explore that thread in a more meaningful way than a traditional memoir.

SN: Did working on this story feed into the addictive, obsessive nature of your personality? I know, for me, writing about anxiety totally feeds into that, but did telling your story kind of scratch that itch in a way? Was it therapeutic?

SL: It was hard at first. I sold the book, and I couldn’t start writing it for a little while. I didn’t touch it. I was paralyzed, and I felt like I couldn’t remember anything that had happened to me when I was drinking. I felt like I was in a blackout, and I remember talking to a therapist about it. Once I scratched the surface and started writing, it did really pour out, and it was cathartic. I wrote late at night. I tried to have a very “adult writing schedule” of getting up and writing first thing in the morning, and I often ended up more like an addict, like a procrastinator, writing all night, alone on the couch. But that’s just how I write, and it was really cathartic. I also was getting married. The day that the first draft of my book was due, my wedding was like the next day. I think, as an alcoholic, I needed the distraction of this book to prevent myself from feeling all the anxiety that could have come with those circumstances. So in a lot of ways, I think the book really saved me. I was able to just hold onto it as an anchor. And throughout writing it, I was continuing to work on my recovery and continuing to do that work as well. So, the whole thing was always one day at a time.

SN: Did this become a part of your therapy in a way?

SL: It did. In recovery meetings, you have these moments where people stand and tell their story, and it was like I was doing that every day as I was working on the book. So, it did become a recovery tool. I think, for me, it was just like telling my story, reminding myself of the fact that I can’t drink safely.

SN: It became a mantra of sorts for you.

SL: Yeah, because our brains play tricks on us. We become unreliable narrators or brands, but you can’t do that when you’re staring at the blank page.

SN: You also say in the book, “By the time I quit drinking, I barely knew who I was.” Do you feel like, after years of working programs and having it all down on paper, you know who you are now, or are you still learning?

SL: I’m definitely still learning. I think the longer I stay sober, in some ways, the less I know. I don’t know if that’s humility or just my mind clearing and making space for new things. I do feel like I know much more about who I am today than I did when I was drinking, but I also feel like there’s a lot of space to continue learning new things about myself. And that’s really exciting too.

When I was drinking, that was all that there was. It was my biggest personality trait. It was like, “I’m a good student. I’m a perfectionist. I try to have things look good on the outside. And I drink. And that’s how I have fun. And that’s how I cope. And that’s everything.” Now, things have softened, and there’s just a little bit more room for figuring new things out. There’s room now in my personality to try new things and make space for different experiences, and that didn’t exist for me before.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Scott Neumyer is a writer from central New Jersey whose work has been published by The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, The Wall Street Journal, ESPN, GQ, Esquire, The Boston Globe, AARP, Parade magazine, and many more publications. You can follow him on Instagram and Twitter @scottneumyer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY