Once again, she held the box of cookies in front of me. I took another cookie but she kept the box there, in the same place. I took yet another cookie, and another until the whole box disappeared. “Can you read what it says there?” she asked, pointing at a line of red letters. “I cannot read American,” I said.

–Edwidge Danticat, “The Missing Piece,” Krik? Krak!

*

This particular child who ate all the cookies is a character in one of Edwidge Danticat’s amazing stories of life in contemporary Haiti and the Haiti of Brooklyn and Miami. Whether we speak or read American, we’ve had a terrible time taking freely from the table of bounty freedom has afforded the other Americans. I often wonder if the move to monolingualize this country is a push for the homogeneity of our foods as well. Once we read American will we cease to recognize ourselves, our delicacies and midnight treats?

There are moments in our past when I have to wonder how did we celebrate, why, with whom? Not Christmas or Easter or Caledonia’s birthday so much as the first night north of the Mason-Dixon line before Sherman’s March, or dry pants and shoes at a clean table in the Rio Grande Valley, having outwitted the border patrol at La Frontera. When we are illicit, what can we keep down, what do we offer the spirits, the trickster, el coyote, who led us from bondage to a liberty so tenuous we sometimes hide for years our right to be?

Frederick Douglass, the great abolitionist, was reluctant to celebrate the Fourth of July, so we can assume that his famous Fifth of July speech was not followed by racks of barbecued ribs and potato salad. Actually, long before Douglass’s disillusion with Independence Day, African-Americans in Philadelphia, the Cradle of Liberty, were wrestling with authorities over who was free to do what. Why would they want to celebrate the American Declaration of Liberation while the Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed the kidnapping of free slaves back to slave states on the word of any white man, was in effect? In Gary B. Nash’s Forging Freedom we learn:

While white abolitionists were withdrawing to the shadows free blacks in Philadelphia continued their political campaign to abolish slavery at both state and national levels, to revoke The Fugitive Slave Act, and to obtain legislation curbing the kidnapping of free blacks … Beginning in 1808, when Congress finally prohibited the slave trade, Absalom Jones and other black preachers began delivering annual thanksgiving sermons on New Year’s Day, the date of the prohibition of trade and also the date of Haitian independence in 1804. The appropriation of New Year’s Day as the black Fourth of July seems to have started simultaneously in Jones’ African Episcopal Church and in New York’s African Zion Church.

And so, black-eyed peas and rice or “Hoppin’ John,” even collard greens and pig’s feet, are not so much arbitrary predilections of the “nigra” as they are symbolic defiance; we shall celebrate ourselves on a day of our choosing in honor of those events and souls who are an honor to us. Yes, we eat potato salad on Independence Day, but a shortage of potatoes up and down Brooklyn’s Nostrand Avenue in July will not create the serious consternation and sadness I saw/experienced one New Year’s Eve, when there weren’t no chitlins to be found.

Like most American families strewn far and near ’cross the mainland, many African-American families, like my own, experience trans–cross Caribbean or Pan-American Highway isolation blues during global/national holidays. One Christmas and New Year’s my parents and siblings were somewhere ’tween Trinidad, Santo Domingo, and Los Angeles. My daughter and I were lucky enough to have a highly evolved horizontal family, that is, friends and associates from different bloodlines, but of the same spirit, reliable, loving, and alone, too, except for us.

Though I ate alone that New Year’s Eve, I knew a calm I must attribute to the satisfaction of my ancestors.

Anyway, this one winter I was determined that Savannah, my child, should have a typical Owens/Williams holiday, even though I was not a gaggle of aunts and uncles, cousins, second and third cousins twice removed, or even relatives from Oklahoma or Carolina. I was just me, Mommy, in one body and with many memories of not enough room for all the toddlers at the tables. How could I re-create the smells of okra and rice, Hoppin’ John, baked ham, pig’s feet, chitlins, collard greens, and corn bread with syrup if I was goin’ta feed two people? Well, actually one and a half people. She woulda counted as a half in the census. But how we are counted in the census is enough to give me a migraine, and I am trying to recount how I tried to make again my very colored childhood and my very “black” adolescence.

So in all of Clinton-Washington where I could walk with my shopping cart (I am truly an urban soul), there were no chitlins or pig’s feet. I remember standing with a very cold little girl right at the mouth of the C train entrance. Were we going on a quest at dusk on New Year’s Eve or were we going to be improvisationally nimble and work something out? I was cold, too, and time was not insignificant. Everything I had to prepare before midnight was goin’ta take all night. Back we went into a small market, sawdust on the floor, and a zillion island accents pushing my requests up toward the ceiling. “A pound and a half of pig tails,” I say. Savannah murmured “pig tails” like I’d said Darth Vader was her biological father.

Nevertheless, I left outta there with my pig’s tails, my sweet potatoes, collards, cornmeal, rice and peas, a coconut, habañera peppers, olive oil, smoked turkey wings, okra, tomatoes, corn on the cob, and some day-old bread. We stopped briefly at a liquor store for some bourbon or brandy, I don’t remember which. All this so a five-year-old colored child, whose mother was obsessed with the cohesion of her childhood, could pass this on to a little girl, who was falling asleep at the dill pickle barrel, ’midst all Mama’s tales about suckin’ ’em in the heat of the day and sharin’ one pickle with anyone I jumped double Dutch with in St. Louis.

Our biggest obstacle was yet to be tackled, though. The members of our horizontal family we were visiting, thanks to the spirits and the Almighty, were practicing Moslems. Clearly, half of what I had to make was profane, if not blasphemous in the eyes/presence of Allah. What was Elegua, Santeria’s trickster spirit, goin’ta do to assist me? Or, would I have to get real colloquial and call on Brer Rabbit or Brer Fox?

As fate would have it, my friends agreed that so long as I kept the windows open and destroyed all utensils and dishes I used for these requisite “homestyle” offerings, it was a go. I’ll never forget how cold that kitchen was, nor how quickly my child fell asleep, so that I alone tended the greens, pig’s tails, and corn bread. Though I ate alone that New Year’s Eve, I knew a calm I must attribute to the satisfaction of my ancestors. I tried to feed us:

Pig’s Tails by Instinct

Obviously, the tails have gotta be washed off, even though the fat seems to reappear endlessly. When they are pink enough to suit you, put them in a large pot full of water. Turn the heat high, get ’em boilin’. Add chopped onion, garlic, and I always use some brown sugar, molasses, or syrup. Not everybody does. Some folks like their pig extremities bitter, others, like me, want ’em sweet. It’s up to you. Use a large spoon with a bunch of small holes to scrape off the grayish fats that will cover your tails. You don’t need this. Throw it out. Let the tails simmer till the meat falls easily from the bones. Like pig’s feet, the bones are soft and suckable, too. Don’t forget salt, pepper, vinegar, and any kinda hot sauce when servin’ your tails. There’s nothin’ wrong with puttin’ a heap of tails, feet, or pig’s ears right next to a good-sized portion of Hoppin’ John, either. Somethin’ about the two dishes mix on the palate well.

Hoppin’ John (Black-eyed Peas and Rice)

Really, we should have soaked our peas overnight, but no such luck. The alternative is to boil ’em for at least an hour after cleaning them and gettin’ rid of runty, funny-lookin’ portions of peas. Once again, clear off the grayish foam that’s goin’ta rise to the top of your pot. Once the peas look like they are about to swell or split open, empty the water, get half as much long grain rice as peas, mix ’em together, cover with water (two knuckles’ deep of female hand). Bring to a boil, then simmer. Now, you can settle for salt and pepper. Or you can be adventurous, get yourself a hammer and split open the coconut we bought and either add the milk or the flesh or both to your peas and rice. Habañera peppers chopped really finely, ’long with green pepper and onion diced ever so neatly.

Is it necessary to sauté your onion, garlic, pepper, and such before adding to your peas and rice? Not absolutely. You can get away without all that. Simmer in your heavy kettle with the top on till the water is gone away. You want your peas and rice to be relatively firm. However, there is another school of cookin’ that doesn’t mix the peas with the rice until they are on the actual plate, in which case the peas have a more fluid quality and the rice is just plain rice. Either way, you’ve got yourself some Hoppin’ John that’s certain to bring you good luck and health in the New Year. Yes, mostly West Indians add the coconut, but that probably only upset Charlestonians. Don’t take that to heart. Cook your peas and rice to your own likin’.

Collard Greens to Bring You Money

Wash 2 large bunches of greens carefully ’cause even to this day in winter critters can hide up in those great green leaves that’re goin’ta taste so very good. If you are an anal type, go ahead and wash the greens with suds (a small squirt of dish detergent) and warm water. Rinse thoroughly. Otherwise, an individual leaf check under cold runnin’ water should do. Some folks like their greens chopped just so, like rows of a field. If that’s the case with you, now is the time to get your best knife out, tuck your thumb under your fingers, and go to town. On the other hand, some just want to tear the leaves up with gleeful abandon. There’s nothing wrong with that, either. Add to your greens that are covered with water either ¼ pound salt pork, bacon, ham hocks, 2–3 smoked turkey wings, 3–4 tablespoons olive oil, canola oil, and the juice of 1 whole lemon, depending on your spiritual proclivities and prohibitions. Bring to a boil, turn down. Let ’em simmer till the greens are the texture you want. Nouveau cuisine greens eaters will have much more sculpted-looking leaves than old-fashioned greens eaters who want the stalks to melt in their mouths along with the leaf of the collard. Again, I add ⅓ cup syrup, or 2 tablespoons honey, or 3 tablespoons molasses to my greens, but you don’t have to. My mother thinks I ruin my greens that way, but she can always make her own, you know. Serve with vinegar, salt and pepper, and hot sauce to taste. Serves 6–8.

I need to know how we celebrate our victories, our very survival. What did we want for dinner? What was good enough to commemorate our humanity?

French-Fried Chitlins

I was taught to prepare chitlins by my third and fourth cousins on my mother’s side, who lived, of course, in Texas. My father, whose people were Canadian and did not eat chitlins at all, told me my daughter’s French-fried Chitlin taste like lobster. Most of the time you spend making these 5 pounds of highfalutin chitlins will be spent cleaning them (even if you bought them “pre-cleaned,” remember, the butcher doesn’t have to eat them!). You need to scrub, rinse, scrub some more, turn them inside out, and scrub even more. By the time you finish, the pile of guts in front of you will be darn near white and shouldn’t really smell at all. Now you are ready to start the fun part. Slice the chitlins into ½-inch strips and set them aside. Prepare a thin batter with ½ cup flour, ½ cup milk, ⅓ bottle of beer—drink the rest—and seasonings to taste (if you forget the cayenne, may God have mercy on your soul!). Heat 2–3 inches of oil or bacon grease—use what you like as long as you don’t use oil that has been used to fry fish—until very hot but not burning (360–375 degrees). Dip each strip into the batter, let excess drip down, and fry until golden brown. Only fry one layer at a time and be sure to move the chitlins around in the pot. After patting away excess grease with a paper towel, serve with dirty rice, greens, and corn bread. Or you can just eat them by themselves on a roll like a po’ boy.

*

But seriously, and here I ask for a moment of quiet meditation, what did L’Ouverture, Pétion, and Dessalines share for their victory dinner, realizing they were the first African nation, slave-free, in the New World? What did Bolivar crave as independence from Spain became evident? What was the last meal of the defiant Inca Atahualpa before the Spaniards made a public spectacle of his defeat?

I only ask these questions because the New York Times and the Washington Post religiously announce the menu of every Inauguration dinner at the White House every four years. Yet I must imagine, along with the surrealistic folk artists of Le Soleil in Port-au-Prince in their depictions of L’Ouverture’s triumph, what a free people chose to celebrate victory. What sated the appetites of slaves no longer slaves, Africans now Haitians, ordinary men made mystical by wont of their taste for freedom? How did we consecrate our newfound liberty? Now this may only be important to me, but it is. It is very important. I need to know how we celebrate our victories, our very survival. What did we want for dinner? What was good enough to commemorate our humanity? We know Haitians are still hungry. Don’t we?

I wake each morning to a canvas by Paul Théaud of a woman, with no body as we understand a human form, walking in a lime green ocean; she is strolling by a lovely, living coral fish. But there on the shore is a young boy whose stomach is missing, simply not there. His face is scrambled with confusion. There is a fish alive, a woman with no body walking in the sea, and he is on shore with no tummy. What does it mean? Maybe Bob Marley can answer us, so we don’t spend years in a daze thinking Dred Scott has transmogrified: “Dem belly full, but dey hungry / A hungry man is a angry man.”

No one told me that to be dangerous one had to be ugly as well. No one told me I had to speak American to know tenderness. Speaking American ain’t necessarily nourishing. I want to know what Grenada’s Socialist prime minister, Maurice Bishop, had for his last meal before the tiny island’s dreams were dashed by American forces in a matter of minutes. Was there anything for him to eat? Is the Haitian woman without a body heading toward New Orleans where the slave ships useta land or is she on her way to Guantanamo Bay, or maybe your back door?

__________________________________

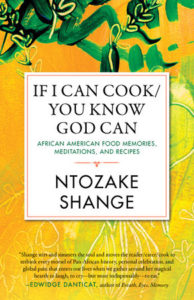

From If I Can Cook/You Know God Can. Used with permission of Beacon Press. Copyright © 2019 by Ntozake Shange.