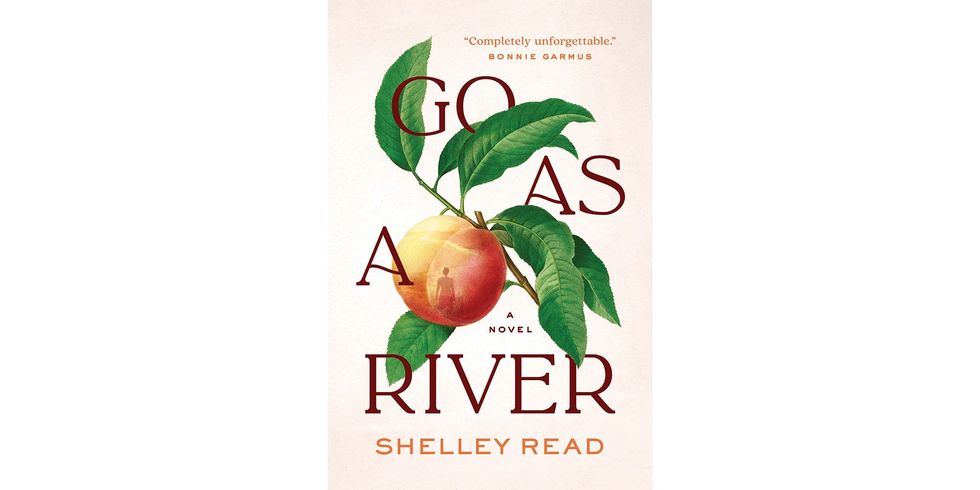

Good and true nature writing in fiction is a delight. But of late, I’ve found that the best descriptions of wilderness are those contained in nonfiction books or confined to the genre known as, well, nature writing. So it was with enormous pleasure that I experienced Shelley Read’s debut novel, Go As a River.

Read skillfully tells the story of Victoria Nash from her teens to adulthood as she navigates love, racism, and heartbreak in the male-dominated world of Iola, Colorado, of the 1940s and ’50s. Iola is destined to be flooded by the damming of the Gunnison River to create a reservoir for hydropower. The prospect of this inevitable “progress” serves as a foreboding presence throughout the narrative. Gone will be the Nashes’ farm, their way of life, and the plants and animals of a beautiful river valley.

Torie is the only woman in a house of men: her weary father, war-scarred uncle, and angry brother. Her plight is to keep house, do a full share of the farmwork, as well as cook and clean for the men. Yet her very small world is upended when she encounters a young Indigenous man in town. It is love at first sight.

Read an excerpt from Go As a River.

Nature plays a leading role throughout the ensuing drama: a not-so-invisible hand that determines the success—or failure—of the Nashes’ peach crop; a welcoming haven when Torie needs to escape into the mountains; an unpredictable, malevolent force that threatens Torie’s survival. What she encounters in the woods, meadows, and mountain streams often reflects her emotions and helps her make sense of her situation. After fleeing home and taking refuge in a small cabin, she builds a rabbit snare and waits:

Bats dove and spun above me, plucking miller moths from midair. Night noises roused cricket by cricket. A doe appeared on the meadow’s edge, tiptoeing from the aspens. She straightened her neck in surprise, blinked, and lightly stamped her feet, unsure what to make of me. Her black eyes glistened and blinked again, and her white tail feathered back and forth in indecision. Still as stone, I gazed at her. I had seen many animals since my arrival—ground squirrels and tree squirrels and bullet-nosed chipmunks; marmots and rabbits and porcupines and foxes and a lone coyote hunting in a field; herds of deer and elk moving across the hillsides—but this doe was the first to seem as interested in me as I was in her. We locked eyes for a long while.

Alta Journal caught up with Read to discuss Go As a River. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

How much of Go As a River is based on personal experience, how much of it required research, and how much of it sprang forth from your imagination?

Well, first of all, it is a work of fiction. And so any of the characters in the novel are completely made up, which is kind of a fascinating thing in and of itself. Like where do these characters come from?

The situations in which they find themselves are based on what I’ve learned from being a fifth-generation Coloradoan and what I’ve learned from my own family’s stories of being homesteaders and ranchers and farmers on the eastern plains of Colorado in the late 1800s and well into the middle of the 20th century.

I did a ton of research around the construction of the Blue Mesa Dam and the flooding of the section of the wild Gunnison River, where the town of Iola once stood, for the creation of Blue Mesa Reservoir, which is the largest reservoir in Colorado. I’ve long known, ever since I was a kid, that there were three towns at the bottom of Blue Mesa Reservoir: Iola, Cebolla, and Sapinero. One of the towns, Sapinero, was actually moved up on a hill. It still exists, sort of. But the others, you know, were erased. They’re completely erased. And so ever since I was very young, the fact that there was a town underneath Blue Mesa Reservoir really captured my imagination.

Much like Iola, the Napa County town of Monticello was flooded in the 1950s and now lies beneath Lake Berryessa. Dorothea Lange and Pirkle Jones documented the plight of the families who were forced to relocate, and they later published their photos in a magazine. For your novel, was there a central document about Iola that you drew from?

In terms of documentation, there’s not a whole lot written about Iola. But we do have some brilliant historians here in our valley and some wonderful museums. The state historical society was a great resource for me as well.

I try to unpack, in a very subtle way, notions of progress in my novel. I certainly couldn’t write a book about Victoria being displaced from Iola without first considering the Indigenous population that was so violently displaced from the same area. And so there’s a little bit of an underlying theme that I don’t hit on too heavily but is very important to me, and that is questioning notions of progress and the human suffering that comes with that.

We want to pretend that all progress is good. My prologue says that a textbook version of the building of the Blue Mesa Reservoir would portray it as heroic, right?

You write about nature so exquisitely, summoning the experience of being alone in the mountains. Which writers of nature do you admire?

I open my novel with an epigram from Annie Dillard. Her Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is a really beloved book for nature writers, but my favorite of hers is Teaching a Stone to Talk, and that’s where I got that quote from.

I love Terry Tempest Williams. She has a similar ancestral connection to Utah that I have to Colorado—our entire lives rooted ancestrally in a place that you feel like you need to both attend to carefully and also defend.

And the poet Mary Oliver, I can’t not mention her. When I was in my PhD program, I wanted to study her, and at the time they were like, “No, a nature poet, nobody’s gonna read Mary Oliver” [laughs]. Since then, she’s really come into prominence. The thing I love about her is her heart. The depth of her love for the natural world is just unsurpassed. And how she can capture that with the most detailed descriptions and observations.

I think that anyone who is openhearted and open-minded when they enter a wild landscape can feel it and write of it with careful attention, and with soul, and with spirit.

You’ve shared with me that you like to go camping alone. Do you ever go into the wild to write?

Always. I don’t have a great memory, but I have great journals [laughs]. It is just page after page after page of me attending carefully to the natural world, and also reflecting on what it incites in me.

Even when I’m backpacking, and you literally are taking a toothbrush that’s only this big, and making sure your food is all dehydrated so that your pack isn’t too heavy, I’ll always bring a notebook and a pen. I will always put that weight in my backpack because I know that something out there is going to move me. That’s where I do my best writing, for sure.

The wilderness can be both welcoming and threatening. Have you had any dangerous experiences in the woods?

Yes, many of what I like to call my near-death experiences, mostly on high mountaintops when unexpected lightning storms move in. The weather in Colorado can change instantly. I incorporate that into my book, in Victoria’s story, how a snowstorm in the middle of the summer really shifts her fate.

I have never had a near-death experience of any sort with a bear, even though I run into them all the time. I think bears get a really bad rap. They are more afraid of me than I am of them. When they see me, they turn and run.

The deeper in the wilderness I am, the higher in elevation I am, the happier I am. It is an unforgiving landscape and so deeply humbling. There’s a quote from the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss that I come back to over and over, and it’s the entire reason I climb big mountains. He says, “The smaller we come to feel ourselves compared with the mountain, the nearer we come to participating in its greatness.”

That really is a guiding light in my life: of participating in that vulnerability and humility so that in a tiny, itty-bitty way, I as a human might participate in what the mountain knows or what the rivers know. It’s really a spiritual endeavor for me.

You’ve mentioned elsewhere that you earned an MFA in creative writing in your 20s, but then instead of continuing to write fiction, you got busy with life for the next 30 years. What led you to create this novel?

Irony is a component of it. I was teaching my students every day, and pouring my heart and soul into it, and cheering them on, and they were saying, “So, Shelley, what have you written lately?”

And I’m like, “Oh. I don’t have time to write.” The irony of that became sort of funny, and then it became kind of painful. I don’t want to live an ironic life.

I never considered myself a novelist when I was in my MFA program. I wrote short fiction, and then after that, I wrote literary nonfiction for magazines and whatnot. Not a lot, but here and there. When I started writing this story, I had no idea it would be a novel. I didn’t know where it would go, I had no idea. Once I started really understanding Victoria’s character, it was a story that I became more and more invested in. It just would not leave me, and I started realizing, “Oh my God. This is a novel.”

Yet I still really didn’t clear space for it until I had a profoundly sad loss, a death in my family. Then my husband had brain surgery. I had a terrible illness. There are certain life experiences like that, that just focus you like a laser beam on what is real and what matters and what does not. I needed to shift my attention to do something new and do something different and do something that I felt was very important to me.

My story of Victoria is very much her becoming herself, and my journey, as a writer, is very much me becoming myself. I just hit a certain point in my becoming where I knew I had to honor my creative spirit.•

Blaise Zerega is Alta Journal's editorial director. His journalism has appeared in Conde Nast Portfolio (deputy editor and part of founding team), WIRED (managing editor), the New Yorker, Forbes, and other publications. Additionally, he was the editor of Red Herring magazine, once the bible of Silicon Valley. Throughout his career, he has helped lead teams small and large to numerous honors including multiple National Magazine Awards. He attended the United States Military Academy, New York University, and received a Michener Fellowship for fiction from the Texas Center for Writers.